Wakefield Tree Survey for Planning.

19th February 2018

Thinking Arbs Day with the Arboricultural Association

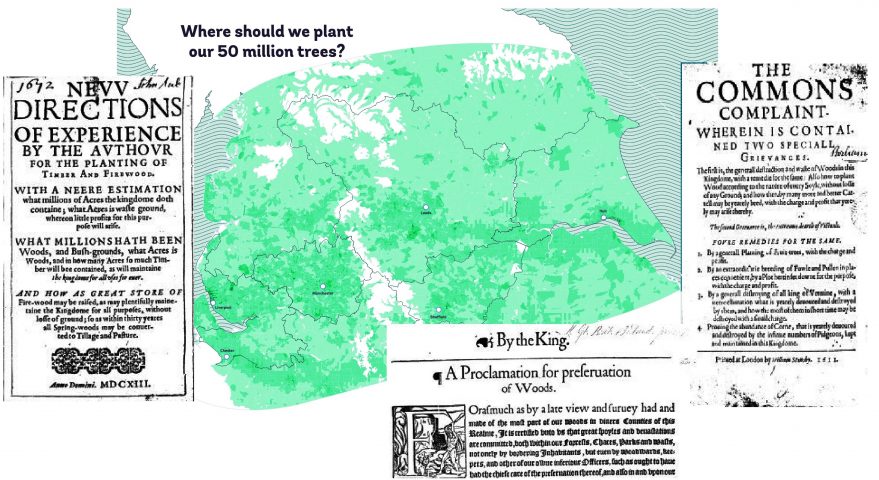

6th March 2018A common wealth of trees? Tree-planting past and present

The Northern Forest: History

The Northern Forest: History

The U.K government recently unveiled plans for ‘The Northern Forest’ – a 25-year tree planting scheme to create a ‘vast ribbon of woodland’ along the M62 corridor from Liverpool and Chester to Hull. The Northern Forest will link up fragmented woodland along the M62 belt and will deliver flood mitigation for up to 190,000 new homes, lock up over 7 million tonnes of carbon, boost wildlife habitat and contribute to northern England’s natural capital and ecosystem services. It is an ambitious scheme that appears to address not only regional and national concerns (e.g. increasing the north of the UK’s tree cover and promoting housing development in a sustainable way with an eye to environmental concerns), but also global concerns regarding climate change.

A similarly ambitious forestry project was undertaken in the 1990s, when 200 square miles of north Leicestershire, south Derbyshire and southeast Staffordshire were planted with trees, to blend ancient woodland with newly planted areas, to create what was termed ‘The National Forest’. However, these projects weren’t the first to consider tree planting across England at such a grand scale and with such political fanfare. AWA Tree Consultant Dr Felicity Stout looks back to the early 17th century, highlighting fascinating parallels to these modern schemes, and their critics.

A proclamation for preservation of woods.

In 1611 Arthur Standish, an English innovator in land management, petitioned James I, ‘we doe in all humbleness complaine unto your Majesty of the general destruction and waste of wood made within this your Kingdome, more within twenty or thirty last yeares then in any hundred yeares before’. He declared that ‘all are given to take the profit present, but few or none at all regard the posteritie or future times’ and explained that there were ‘too many destroyers, but few or none at all doth plant or preserve’. He drew attention to the links between social and economic poverty (especially in the Midlands and North) and wood scarcity and the destruction of trees.

Standish’s pro-active solution to England’s perceived crisis in wood resources was to plant more trees, in an orderly fashion, with attention to what type of soil each species should be planted in, in order to maintain and increase England’s most important natural resource for the future. What was novel about Standish’s scheme was the tree-planting itself. In this period, planting trees was not commonplace, and certainly not on the scale, nor in the structured, plantation-style method that Standish, the pioneer forester, was proposing.

In what Standish called ‘our destroying age’, his innovative directions on planting trees were ‘intended to the good of your Majestie and your Royall progenie, [and] to the general good of the Common-wealth for all posteritie’. He concluded that ‘This kind of planting may be effected with so small a charge, and maintained with so little labour, as not any man that either regardeth the content of their King, the good of their owne posteritie, or Common wealth, can in reason omit to observe [New Directions, 1616, p.1].

Standish’s work was explicitly supported by James I, who went so far as to declare that if Standish’s schemes were ‘put in practise, according to the true intent and meaning thereof, it shall much content Us’, implying that favour might be shown to those who took up Standish’s recommendations to plant trees.

For this, and for the several other royal proclamations regarding the scarcity of wood and the preservation of trees, James I has been seen by some as a ‘conservationist’ and a pro-active interventionist into issues of natural resource management. For instance, in 1609 James issued A proclamation for preservation of woods, in which he expressed great concern at the destruction and decay of woods, declaring that ‘great spoyles and devastations are committed … within our forests … as without present reformation, there is like suddenly to follow such want of Timber and wood as by no future providence can be in meet time supplied’. The proclamation foregrounded the importance of preserving wood and timber ‘for the future’, but was James a proto-conservationist, concerned with ‘sustainability’? Or simply using the emotive subject of wood scarcity in the present and wood for future generations to try to manage the depletion of his own land and to distract from the fact that he was leasing out vast swathes of crown woodland to exploitative and destructive industries in order to raise revenue for his luxurious lifestyle?

Trees are profoundly political.

These questions are all vaguely interesting, you may say, but so what? Well, James I’s talk of ‘posteritie’ and concern for ‘future generations’ of people, trees, and wood resources (whilst simultaneously allowing extensive destruction of trees on crown land), resonated for me with the current Environment Secretary, Michael Gove’s response to the Northern Forest project, unveiled in January: “Trees are some of our most cherished natural assets and living evidence of our investment for future generations”.

The discourses already surrounding the Northern Forest – from the Woodland Trust’s community forestry-led, ‘bottom-up initiative’ to the government’s emphasis on cherishing natural assets for posterity and future generations – are telling. Trees, tree-planting and the benefits that trees bring to society are profoundly political. Indeed forests and forestry are intimately linked to policy and politics and to the sustaining of the nation – historically through access to the natural resource of wood; and in the present for the ecosystem services and natural capital that they can deliver. Trees make the nation resilient, maintaining the wellbeing of society and the environment for now and for the future. However, trees are also a profoundly emotive subject – both their destruction and their planting – and thus open to gross exploitation by unscrupulous politicians (or kings!).

The Northern Forest, for all the benefits it will bring, is a very convenient vehicle for the government to distract attention away from the 98 ancient semi-natural woodlands that have been threatened with destruction by the building of HS2.

It is also a very cheap way for the government to meet its targets to increase tree cover in the UK, particularly in the north of the country, and to demonstrate that it is responding to the threat of future flooding and a changing climate. The government is stumping up a mere £5.7million to kick-start the project, yet the rest of the £500 million cost for the scheme will have to be raised by charity. Austin Brady (Woodland Trust) hopes that some of the cost of the Northern Forest might be covered by funds allocated for mitigating the environmental impact of major transport projects expected in the north, such as road-building and HS2. Yet as Paul de Zylva from Friends of the Earth pointed out to the BBC “It is a supreme irony that tree planters [for the Northern Forest] will have to get funding from HS2, which threatens 35 ancient woodlands north of Birmingham … You simply can’t compare the biodiversity value of new sticks in the ground with ancient forest … If the government really cared about woodlands it wouldn’t be routing a high speed train through them. And it wouldn’t be allowing the weight of this project to be carried by charity” (BBC News).

We shouldn’t be tricked into thinking a government that jumps on the bandwagon of the Northern Forest really cares about the long-term management, maintenance, and protection of these trees for future generations (especially when they are complicit in destroying irreplaceable ancient semi-natural woodlands). A mass planting scheme such as this needs to be held to account and only time will tell whether the Northern Forest can and will be the panacea for the North it is claimed to be. The trees, be they ancient oaks or mere saplings, are our common wealth and as Standish would say, ‘no wood, no kingdom’.

UPDATE:

Arb Magazine

Since this blog was posted, it has been published in ‘The ARB Magazine’: The Quarterly Publication for Members of the Arboricultural Association as part of the ‘Science and Opinion’ section. This printed version of the article included a response from The Woodland Trust. Their lead campaigner Oliver Newham responded:

The woodland trust remains a staunch defender of our irreplaceable ancient woodland and ancient trees – we will continue to challenge their damage and loss in all circumstances from major projects like HS2 to individual planning applications – that’s our position, and it remains non-negotiable. We think it’s fair to say that no one does more than us in this arena, as our dogged fight to protect ancient woodland throughout the HS2 process to date has demonstrated.

We can categorically state the Woodland Trust will not be applying for funds from HS2 to support either the Northern Forest or any other woodland creation scheme. That does not preclude any of the organisations or community groups we work with from doing so, but we are resolute that we cannot justify using money from a project that rides roughshod over woods and trees.